Interested in learning more about my theory of love and how to apply it to YOUR relationship? Check out my new website here.

Duplex Theory of Love: Triangular Theory of Love and Theory of Love as a Story

The duplex theory of love integrates what previously were two separate theories: the triangular theory of love and the theory of love as a story.

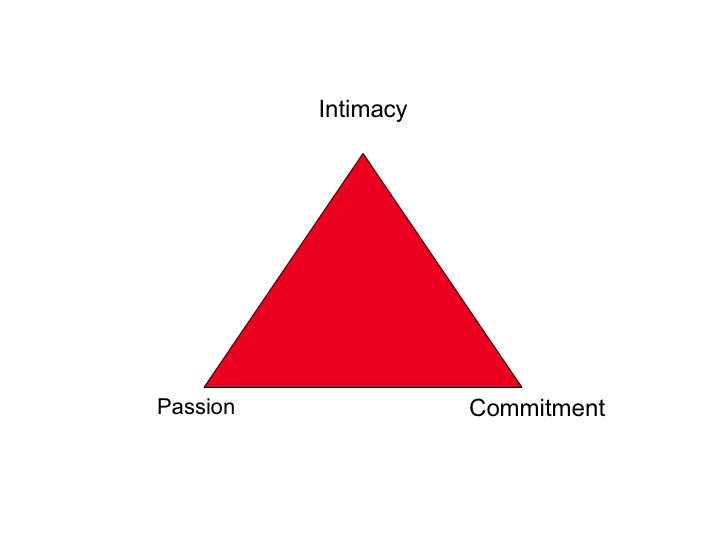

Triangular Theory of Love

The triangular theory of love holds that love can be understood in terms of three components that together can be viewed as forming the vertices of a triangle. The triangle is used as a metaphor, rather than as a strict geometric model. These three components are intimacy, passion, and decision/commitment. Each component manifests a different aspect of love.

Intimacy. Intimacy refers to feelings of closeness, connectedness, and bondedness in loving relationships. It thus includes within its purview those feelings that give rise, essentially, to the experience of warmth in a loving relationship.

Passion. Passion refers to the drives that lead to romance, physical attraction, sexual consummation, and related phenomena in loving relationships. The passion component includes within its purview those sources of motivational and other forms of arousal that lead to the experience of passion in a loving relationship.

Decision/commitment. Decision/commitment refers, in the short-term, to the decision that one loves a certain other, and in the long-term, to one's commitment to maintain that love. These two aspects of the decision/commitment component do not necessarily go together, in that one can decide to love someone without being committed to the love in the long-term, or one can be committed to a relationship without acknowledging that one loves the other person in the relationship.

The Love Triangle

The three components of love interact with each other: For example, greater intimacy may lead to greater passion or commitment, just as greater commitment may lead to greater intimacy, or with lesser likelihood, greater passion. In general, then, the components are separable, but interactive with each other. Although all three components are important parts of loving relationships, their importance may differ from one relationship to another, or over time within a given relationship. Indeed, different kinds of love can be generated by limiting cases of different combinations of the components.

The three components of love generate eight possible kinds of love when considered in combination. It is important to realize that these kinds of love are, in fact, limiting cases: No relationship is likely to be a pure case of any of them.

Nonlove refers simply to the absence of all three components of love. Liking results when one experiences only the intimacy component of love in the absence of the passion and decision/commitment components. Infatuated love results from the experiencing of the passion component in the absence of the other components of love. Empty love emanates from the decision that one loves another and is committed to that love in the absence of both the intimacy and passion components of love. Romantic love derives from a combination of the intimacy and passion components. Companionate love derives from a combination of the intimacy and decision/commitment components of love. Fatuous love results from the combination of the passion and decision/commitment components in the absence of the intimacy component. Consummate, or complete love, results from the full combination of all three components.

The geometry of the "love triangle" depends upon two factors: amount of love and balance of love. Differences in amounts of love are represented by differing areas of the love triangle: The greater the amount of love, the greater the area of the triangle. Differences in balances of the three kinds of love are represented by differing shapes of triangles. For example, balanced love (roughly equal amounts of each component) is represented by an equilateral triangle.

Love does not involve only a single triangle. Rather, it involves a great number of triangles, only some of which are of major theoretical and practical interest. For example, it is possible to contrast real versus ideal triangles. One has not only a triangle representing his or her love for the other, but also a triangle representing an ideal other for that relationship. Finally, it is important to distinguish between triangles of feelings and triangles of action.

Theory of Love as a Story

Love triangles emanate from stories. Almost all of us are exposed to large numbers of diverse stories that convey different conceptions of how love can be understood. Some of these stories may be explicitly intended as love stories; others may have love stories embedded in the context of larger stories. Either way, we are provided with varied opportunities to observe multiple conceptions of what love can be. These stories may be observed by watching people in relationships, by watching media, or by reading fiction. It seems plausible, that as a result of our exposure to such stories, we form over time our own stories of what love is or should be.

Various potential partners fit our stories to greater or lesser degrees, and we are more likely to succeed in close relationships with people whose stories more rather than less closely match our own. Although fundamentally, the stories we create are our own, they draw on our experience of living in the world--on fairy stories we may have heard when we were young, from the models of love relationships we observe around us in parents and relatives, from television and movies, from conversations with other people about their relationships, and so forth.

Although the number of possible stories is probably infinite, certain genres of stories seem to keep emerging again and again in pilot analyses we have done of literature, film, and people’s oral descriptions of relationships. Because the stories we have analyzed were from participants in the United States, our listing is likely to show some degree of cultural biased.

Stories we have found to be particularly useful in conceptualizing people's notions of love are

1. Addiction. Strong anxious attachment; clinging behavior; anxiety at thought of losing partner.

2. Art. Love of partner for physical attractiveness; importance to person of partner's always looking good.

3. Business. Relationships as business propositions; money is power; partners in close relationships as business partners.

4. Collection. Partner viewed as "fitting in" to some overall scheme; partner viewed in a detached way.

5. Cookbook. Doing things a certain way (recipe) results is relationship being more likely to work out; departure from recipe for success leads to increased likelihood of failure.

6. Fantasy. Often expects to be saved by a knight in shining armor or to marry a princess and live happily ever after.

7. Game. Love as a game or sport.

8. Gardening. Relationships need to be continually nurtured and tended to.

9. Government. (a) Autocratic. One partner dominates or even controls other. (b) Democratic. Two partners equally share power.

10. History. Events of relationship form an indelible record; keep a lot of records--mental or physical.

11. Horror. Relationships become interesting when you terrorize or are terrorized by your partner.

12. House and Home. Relationships have their core in the home, through its development and maintenance.

13. Humor. Love is strange and funny.

14. Mystery. Love is a mystery and you shouldn't let too much of yourself be known.

15. Police. You've got to keep close tabs on your partner to make sure he/she toes the line, or you need to be under surveillance to make sure you behave.

16. Pornography. Love is dirty, and to love is to degrade or be degraded.

17. Recovery. Survivor mentality; view that after past trauma, person can get through practically anything.

18. Religion. Either views love as a religion, or love as a set of feelings and activities dictated by religion.

19. Sacrifice. To love is to give of oneself or for someone to give of him or herself to you.

20. Science. Love can be understood, analyzed, and dissected, just like any other natural phenomenon.

21. Science Fiction. Feeling that partner is like an alien--incomprehensible and very strange.

22. Sewing. Love is whatever you make it.

23. Theater. Love is scripted, with predictable acts, scenes, and lines.

24. Travel. Love is a journey.

25. War. Love is a series of battles in a devastating but continuing war.

26. Student-teacher. Love is a relationship between a student and a teacher.

Key References

Sternberg, R. J., & Grajek, S. (1984). The nature of love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 312–329.

Sternberg, R. J., & Barnes, M. (1985). Real and ideal others in romantic relationships: Is four a crowd? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 1586–1608.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93, 119–135.

Sternberg, R. J. (1987). Liking versus loving: A comparative evaluation of theories. Psychological Bulletin, 102, 331–345.

Sternberg, R. J. (1988). Triangulating love. In R. J. Sternberg & M. Barnes (Eds.), The psychology of love (pp. 119–138). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1988). The triangle of love. New York: Basic.

Sternberg, R. J. (1994). Love is a story. The General Psychologist, 30(1), 1–11.

Beall A. E., & Sternberg, R. J. (1995). The social construction of love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(3), 417–438.

Sternberg, R. J. (1995). Love as a story. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12 (4), 541–546.

Sternberg, R. J. (1996). Love stories. Personal Relationships, 3, 1359–1379.

Barnes, M. L., & Sternberg, R. J. (1997). A hierarchical model of love and its prediction of satisfaction in close relationships. In R. J. Sternberg, & M. Hojjat (Eds.). Satisfaction in close relationships (pp. 79–101). New York: Guilford Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology , 27(3), 313–335.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Cupid’s arrow: The course of love through time. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Love is a story. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., Hojjat, M., & Barnes, M. L. (2001). Empirical aspects of a theory of love as a story. European Journal of Personality, 15(3), 199–218.

Sternberg, R.J. (2006). A duplex theory of love. In R. J. Sternberg & K. Weis (Eds.), The new psychology of love (pp. 184–199). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sternberg, R. J. (2013). Measuring love. The Psychologist, 26(2), 101.

Sternberg, R. J. (2013). Searching for love. The Psychologist, 26(2), 98-101.